PARKS OF PEACE

(published in the Mail and Guardian)

Click to download in pdf format:In November 2000 the three governments of South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe signed an agreement that was unprecedented in the history of African conservation. The formation of the Gaza-Kruger-Gonarezhou (GKG) Trans-Frontier Park not only committed each country to advancing the cause of African conservation and regional development, it should also secure the future for one of the largest wilderness areas in the world.

The planned 'peace park' includes a large slice of state owned land in Mozambique's Coutada 16 conservation area in Gaza Province, South Africa's showcase Kruger National Park plus adjacent private reserves, and Zimbabwe's second largest game park, the Gonarezhou National Park and its wildlife environs. In total the area concerned is about the size of the Netherlands, covering just over 35,000 square kilometres.

It is also intended that much of the Park's surrounding land will be included into a wider Trans-Frontier Conservation Area (TFCA) in which similar wildlife-based land uses will be conducted by a variety of private and communal landowners under some form of joint management umbrella. In addition to promoting local bio-diversity, one of the project's most important aims is to ensure surrounding communities directly benefit from their proximity to the GKG park, raising regional living standards through the sustainable use of wildlife. Zimbabwe's Minister of Environment and Tourism, Francis Nhema, declared, 'We need to develop management plans for these targeted TFCAs which will woo the essential investment, create the smart partnerships symbolized by mutual benefits and provide political leadership and an enabling environment for such developments to be a reality'. In his closing remarks he stated, 'If we succeed in this initiative I expect that the Gaza-Kruger-Gonarezhou Trans-Frontier Park cannot only be seen as a symbol of regional co-operation among our countries but can be viewed as a 'showcase', which other states on our continent will emulate'.

Whilst the agreement was being signed, sections of Zimbabwe's 'showcase' had been occupied, cleared and set alight by neighbouring villagers and so-called 'war veterans'. It was to become the latest in a line of crises to hit Zimbabwe's wildlife since the current 'fast-track' resettlement programme had begun to involve key conservation areas on private land.

As a member of this great 'peace park', it is ironic that historically Gonarezhou has rarely been at peace. In Shona, 'gona-re-zhou' means 'abode of elephants', but for the elephant it sadly has not been a safe abode as poaching has always been prevalent in this south-eastern corner of Zimbabwe. In the late 1960s large-scale agriculture began encroaching on this 'home of the elephants' and poaching coupled with tsetse fly controls that included bush burning and shooting, resulted in 55,000 large animals being destroyed. In response, Alan Wright, a local District Commissioner, helped establish a wildlife refuge and a poaching control corridor along the Mozambique border. 5000 square kilometres of prime wilderness became designated as a reserve, and in 1975 this corner of Zimbabwe was declared a National Park.

Whilst this should have heralded happier times for the region, the local Shangaan people were forced to resettle outside the park's boundaries - an act that has caused major discontent in the area ever since. Sadly, the formation of a park also did little to stop the unnatural deaths of the resident elephants. During the Rhodesian war of independence, an extensive network of land mines were laid down in Gonarezhou and dozens of elephants are reported to have died as a result. In more recent times elephants and buffaloes have had to be killed after they were maimed by land mines still lying within the park. During the 1980s and '90s poaching by Mozambican guerrillas, fighting their own civil war across the border, also took its toll. It is estimated that between 1987 and 1988 nearly 1000 elephant and 200 black rhino were poached from the park (and there is some evidence to suggest that Renamo forces were not the only culprits, the Zimbabwean Army and Airforce are also thought to have had a hand in this massacre). Driving through the park today, it is not surprising that the Gonarezhou elephant responds to human presence with either fear or aggression.

After such a disturbing history, this 'park of peace' is experiencing yet another battle which could threaten one of the biggest and boldest conservation initiatives the world has ever seen. Josiah Hungwe, the notorious Governor of Masvingo who is already responsible for the invasions of privately owned wildlife conservancies, has been encouraging families of the previously evicted Shangaan, as well as opportunistic 'war veterans' to take over 11,000 hectares within Gonarezhou north and south of the Runde river. Given the government's blessing, the situation escalated as Agritex (the Agricultural and Rural Extension Department) officially began demarcating and pegging out plots for allocation within the Park.

It appeared that the whole invasion had been carried out without the permission - or knowledge - of the Ministry for Environment and Tourism. In fact Francis Nhema initially denied the incident altogether - "There is nothing like that. What has happened is that some cattle strayed into the park but our guys from Parks are working on that. There are no people physically within the park at all."

It soon became apparent that Nhema had been very wrong. In alarm, a senior National Parks officer wrote the following in a letter to his headquarters shortly after the takeover, "The Agritex Officer stated that his teams pegged some 520 plots but the area had capacity to take 750 settlers…

Cattle are being grazed daily inside the park. The numbers are never less than 500 in the park per day. The cattle fence has been put down allowing free movement of cattle in and around the park."

Not only does the invasion threaten the Trans-Frontier agreement, the removal of fencing, and crossing of cattle into buffalo land, is in complete violation of European Union livestock management regulations. Mike Clark, Regional Chairman of the Masvingo Commercial Farmers Union, points out, "This cattle movement into buffalo territory comes at a time where we have no foot and mouth vaccine due to the forex shortage. We have been sitting on a foot and mouth time bomb, not to mention food riots - all in the name of politics, which does not feed people." Zimbabwe is now paying for her land grabs and foot and mouth has indeed broken out signalling the end of the Zimbabwean beef export industry.

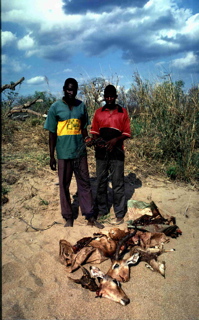

On a personal visit to investigate the situation last November, I found cattle grazing in the park and substantial destruction of natural habitat in the northern section of the park to the west of the Chihunja mountain range in an area that was once mopane woodland and prime elephant country. On our drive through the park, the entire area from Chipinda pools to the foothills of the Chilojo cliffs a distance of about 40 kilometres, lay burning or burnt. Countless numbers of the taller, older trees had been burnt through to their roots and several had crashed to the ground over the road, forcing us to drive around them. An elephant, terrified at the sight of humans, thundered through the blackened cinders, its favourite browsing area no more than a smoking mass of black earth. At night we could see new fires starting on the hills. The next day I asked one of the game scouts how the fires had started, he said 'poachers'. He went on to tell me that they didn't have the resources to fight the fire and that this was one of the worst years he'd ever seen - 'it's been very bad and lots of animals have died'. We saw one parks' vehicle over the two days that we were in Gonarezhou. It was a pick-up with three people in the front and three in the back, they were off-road and appeared to be chasing a herd of impalas. On seeing us they stopped and waved and waited for us to go out of sight.

Amongst the bustle of huts and villages under construction in the resettlement area, a group of people gathered around our car. They confirmed that 750 people were settling here from the Sangwe Communal area. They were hoping to set up a CAMPFIRE system whereby the community benefits from the exploitation of wildlife and tourism. They were also intending to grow cotton in the area. (A farmer has since pointed out to me that cotton is an aggressive feeder and if not fertilised the soil will become barren within 5 years. In order to fertilise they will need intensive irrigation, hardly a consideration in this drought-prone district). Altogether there are 10 villages each person having 5 hectares. When asked about the elephants we were told that the problem animal control people would deal with them if they tried to take their crops.

Further on we picked up a war veteran who proudly showed me his white plastic card with his photo and the words 'Liberation War Hero' printed over the front. We asked him what they were going to plant and he said cotton and some maize. When were they going to plant? Weren't the rains coming soon? 'We're waiting to be told' he replied. Told by whom, I asked? 'Governor Hungwe' was his answer.

On the northern border of the park is land owned by the Malilangwe Trust. The aim of the trust is to restore and maintain the area's biodiversity as well as make a material and lasting contribution to the development of the lowveld. It has already made a recognised contribution to the conservation of habitat and wildlife (especially endangered species), and its promotion of sustainable development within the communal areas has been significant.

Malilangwe, Save and Chiredzi River Conservancy are key areas adjacent to Gonarezhou. They, and the communities involved in the various CAMPFIRE and trust projects, all stand to benefit from the GKG project as long as the corridor that joins them with the park remains free of human settlement. Once the peace park is operational, there is enormous potential in creating a wider TFCA extending into these private and communal lands. Derek de la Harpe, Director of Malilangwe points out, 'Any development isolating Malilangwe and the conservancies from the Park will in the long term be to everyone's detriment. Malilangwe is committed to assisting with restocking the Park once our own wildlife populations have been restored to an acceptable level. This will not be possible if the connection between the two areas is cut.'

It is important to realise that most of the wildlife in this corner of the country is not in Gonarezhou, it's in the conservancies. Most of the people who could benefit from the TFCA are also in areas surrounding the conservancies. Most of the investment into tourist facilities won't be in the national parks it'll be by private individuals in the conservancies and on the surrounding community lands.

Derek de la Harpe explains, 'Gonarezhou is a park on paper and not much else. It's desperately in need of restocking. There's absolutely no infrastructure there, poaching is out of control and it only receives 5000 visitors a year. In the short term, the reality is the TFCA needs us - the wildlife and the tourists will have to come from us, and our neighbours. In the long term, the lack of infrastructure, lack of air services and general apathy can all be sorted out by the TFCA. We've never been given an opportunity like this - it's critical to take advantage of it now. By putting people on land where they're going to have food aid for 3 out of every 5 years is no solution. The land grab is not for the benefit of the poor, it's rather destroying the country's agricultural and wildlife base.'

However these issues are clearly not being debated - or even considered - in Zimbabwe's political scramble for land. Instead of limiting the invasion to a controllable area, it has now been extended along the park boundary, past the Sangwe Communal Land and Chizvirizvi Resettlement Area, and along the boundary with Malilangwe. On our visit, the boundary fence on the Gonarezhou side had been taken down, the land burnt and cleared. As well as substantially narrowing the necessary corridor into Malilangwe, the resettlement is successfully isolating Chizvirizvi from the park. The community were hoping to involve themselves in a wildlife and tourism project based on the proposed TFCA. If their land does not adjoin the park there is little chance of that happening. They will be just one of several communities which will suffer from the development as it currently stands. At the moment, the worst affected land from the invasions borders on to this community.

Rob Style from Chiredzi airs his concerns, 'If the aim was to prevent the country from benefiting from the Peace Parks project, it couldn't have been better planned.' The Chairman of Chiredzi Conservancy, Digby Nesbitt, sums up the effects of the land invasions, 'The wildlife industry is so delicate. Trees that take 100s of years to grow are being chopped down, breeding herds slaughtered. In 1992 government helicopters were involved in saving dying animals and everyone in the country tried to keep the game alive - that same game is now being slaughtered and no one in government is lifting a finger to stop it. The whole thing's been motivated by a government trying to stay in power, it doesn't matter if the economy collapses or people starve, it's just a case of staying in power at any cost. It's a crisis situation and we need immediate action. The longer we wait the more animals are being killed and the less likely it'll be that we can ever make use of wildlife in this country's economy. All we want to do is preserve the little bit that's left. The wildlife can't wait until the next election, by then it will be too late.'

As we left the park I couldn't help reflect on the irony of the sign at the park gate: 'Take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints, kill nothing but time'.

January 2001